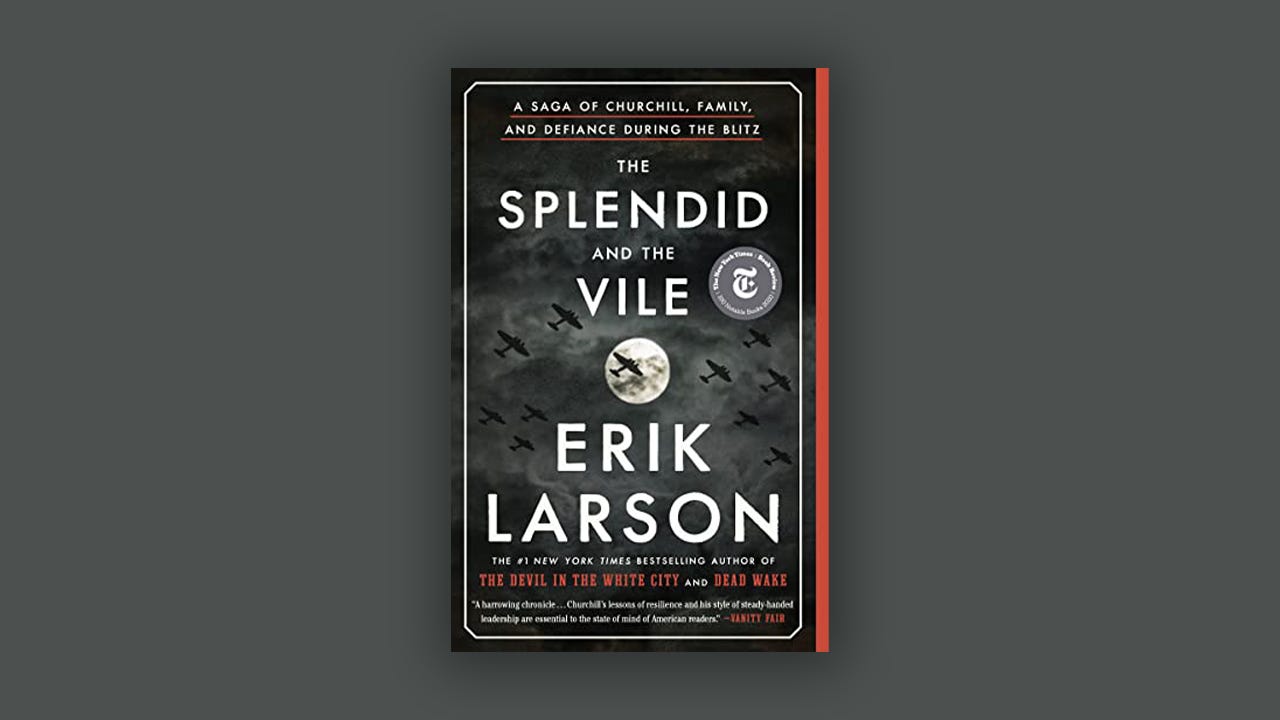

As if it were a movie, The Splendid and the Vile captures the courage and hope of Winston Churchill – the newly minted Prime Minister – his family, close associates, and other Londoners during The Blitz, a nine-month rampage of German bombings on the capital of the United Kingdom during World War II.

I cried. I laughed. I learned.

I sat filled with sorrow about what it must have been like to live during those nine months when death rained from the skies above – every night – while the sun set on the once-quiet town as it tried to hide in a cloak of darkness.

Here’s what I learned about life and human nature.

1. Withholding bad news makes the bad news worse

When Winston Churchill heard of the bombing and subsequent sinking of the RMS Lancastria, where over 4,000 lives were lost, he barred the press from reporting on it. “The newspapers have got quite enough disaster for today at least,” he said. The press was quiet for a while, but after 2,500 survivors arrived in Britain out of nowhere, people started asking questions. Eventually, The New York Times ran the story.

The Home Intelligence Agency, an organization responsible for monitoring British sentiment during the war, reported, “The withholding of the news of the Lancastria is the subject of much adverse criticism. The blatant censorship led the public to imagine what other bad news was being hidden from them.”

In times of war, morale is one of the most important things for survival. Churchill and the government worked hard to keep morale high, often increasing the tea limit to keep people happy. But more tea couldn’t make up for the government’s deceptiveness. In an effort to protect sentiment, the government only caused more damage by not reporting the bad news in a timely manner.

When you break something and wait to fix it, it usually makes it worse. When you do something wrong and don’t own the mistake immediately, it usually makes it worse. If you have bad news to report and don’t, it usually makes it worse.

When you try to hide something, it only makes people look harder for it. (See also: The Streisand Effect.)

2. Give people public attention for doing what you want more of

After the citizens of Jamaica, then a British colony, sent money to help build a bomber, Lord Beaverbrook, the Minister of Aircraft Production, ensured this act of unprompted kindness got widespread attention. Soon, more gifts arrived.

He realized this could generate cash but also boost the morale of the public and the workers building the planes. He sought more donations but never directly asked for them. Rather, Erik Larson writes, “he made a deliberate show of acknowledging those that arrived. When donations reached a certain level, the contributors could choose to name a specific fighter; a richer total allowed the donors to name a bomber.”

Eventually, the BBC gave recognition to the donors on its nightly broadcasts. In the beginning, Beaverbrook wrote a personal letter to each donor, but once this became impossible, he chose the gifts most worthy of attention based on sacrifice, not amount. Larson writes, “A child giving up a few pence was as likely to get a letter as was a rich industrialist.” By May 1941, the donations totaled ~ 13 million pounds ($832 million). Though that amount barely made a dent in the overall production of planes, that wasn’t the point. “To countless men and women,” Beaverbrook’s secretary David Farrer wrote, “he made easy the way to a more personal interest in the war and to an enthusiastic contribution to its waging.”

Instead of trying to get on the BBC every night and saying, “Donate! Donate! We need help!” He gave people public recognition for doing so already. The people that donated became quasi-celebrities, and everyone wanted to be a celebrity, so lots of people donated.

Praise people (in public) for doing what you want more of. If you want employees to come to the office (I hope you don’t), instead of emailing them every week telling them to come, offer perks, shoutouts, and recognition to those who already do. If you want your kid to behave differently, give their sibling public attention for behaving that way.

It's human nature to want attention.

3. A project with more than one owner will fail

Public shelters were home to many during the bombings but were a humane disaster. Liquids that shouldn’t be on the ground were because of the lack of “latrines.” Some latrines were right next to where people slept. Worst of all, there were no provisions for making tea!

Clementine, Churchill’s wife, told the Prime Minister these circumstances were unacceptable. She believed the problem was that too many agencies with overlapping authority were in charge of the shelters, resulting in nothing actually getting done. Quoting her, Larson writes, “‘The only way to get the matter straightened out is to have one authority for safety, health, and everything else’, she wrote to the Prime Minister (carefully calling him his title and not Winston). ‘Division of authority is what is preventing improvement.’”

A dog with two owners dies of starvation.

Division of authority is what is preventing improvement. – Clementine Churchill

4. What’s right for your people may not be the most efficient

One thing that had infuriated Londoners during the night raids wasn’t just the bombings; it was the fact that the Luftwaffe could come and go as they wished. The fact that the RAF was essentially blind at night was one reason the Luftwaffe flew with ease, but not the only one. Also helping their continual raids were the orders for anti-aircraft guns to conserve ammunition and only fire when planes could actually be seen in the sky, which was difficult to do at night. This upset many Londoners; they felt they were being walked all over.

“On Churchill’s orders,” Larson writes, “more guns were brought to the city, boosting the total to nearly two hundred, from ninety-two.” Churchill followed by giving the orders to fire at will, disregarding the previous understanding to conserve ammunition. Though Churchill knew anti-aircraft guns rarely did any damage to German bombers, “The impact on civic morale was striking and immediate,” Larson writes.

Yes, the constant shooting and bombing from the anti-aircraft guns made sleeping nearly impossible, but that didn’t matter. Private secretary John Martin wrote, “Tails are up and, after a fifth sleepless night, everyone looks quite different this morning–cheerful and confident. It was a curious bit of mass psychology–the relief of hitting back (emphasis mine).” The Home Intelligence reported the same, “The dominating topic of conversation today is the anti-aircraft barrage of last night. This greatly stimulated morale: in public shelters, people cheered and conversation shows that the noise brought a shock of positive pleasure.”

Did they waste a lot of ammunition? Positively so. Was it harder to sleep? Most definitely. But were the people happy? Yes. And that’s what mattered most.

A similar thing happened with COVID. Was quarantining, wearing masks, and shutting businesses down the safest thing to do? Yes, it probably was. But was it worth the anger, unhappiness, loneliness, isolation, social unrest, and other second-order effects it caused…?

5. Opinions are useless if you don’t have anything with which to back them up

While working from his room at 10 Downing, Churchill learned that two bombs had fallen adjacent to the house but failed to detonate (that was a common occurrence). “Will they do us any damage when they explode?” He asked John Colville, one of his private secretaries.

“I shouldn’t think so, sir,” Colville replied.

“Is that just your opinion, because if so, it’s worth nothing,” Churchill roared back. “You have never seen an unexploded bomb go off. Go and ask for an official report.”

This, Larson writes, “reinforced for Colville the folly of offering opinions in Churchill’s presence, ‘if one has nothing with which to back them.’”

What’s that saying about people’s opinions?

Is that just your opinion, because if so, it’s worth nothing. – Winston Churchill

6. Your reputation takes a lifetime to build, but you can lose it in a second

Lord Beaverbrook resigned from his post as Air Minister three times by the start of 1941. Each time, he got a bit more serious, yet Churchill was able to persuade him to stay on; his patience, however, was waning.

Churchill wrote Beaverbrook after this third resignation attempt: “My Dear Max, I am very sorry to receive your letter. Your resignation would be quite unjustified and would be regarded as desertion. It would in one day destroy all the reputation that you have gained and turn the gratitude and goodwill of millions of people to anger. It is a step you would regret all your life.”

7. Be in a relationship with someone because you want to be

Clementine Churchill gave Mary, her daughter, sound advice for marriage: “Don’t marry someone because they want to marry you–but because you want to marry them.”

Read more notes on [The Splendid and The Vile here](https://www.dltn.io/posts/the-splendid-and-the-vile).

Tagged